In your classroom, students should feel a sense of significance, belonging, and fun—three crucial components for their success in and out of school. Teachers spend a lot of time readying their classroom community for learning tasks and building a strong academic foundation for students. But the school day is also a crucial time for making connections with peers and sowing the seeds of friendships that will sustain and support students for years to come.

Just like a garden, peer connections thrive much better when they are tended. Here are ten ways to nurture a friendship-ready classroom.

Start and end your day together as a class. Whether it’s a Morning Meeting, a Responsive Advisory Meeting, or a closing circle, coming together as a class at the beginning and the end of the day lays the groundwork for healthy interactions during the school day and beyond. When you sit together in that circle, every student is seen and heard, and every student can see and hear how you model friendly behaviors. While the elements of these meetings may seem simple, they reinforce lifelong skills for making and keeping friends. Students learn to greet each other by name, share appropriately about themselves, listen actively while others share, and work together to achieve success. Those skills are important to teach any time, but it’s a powerful practice to start and end the day by emphasizing what’s most important: caring, respectful connections with their classmates.

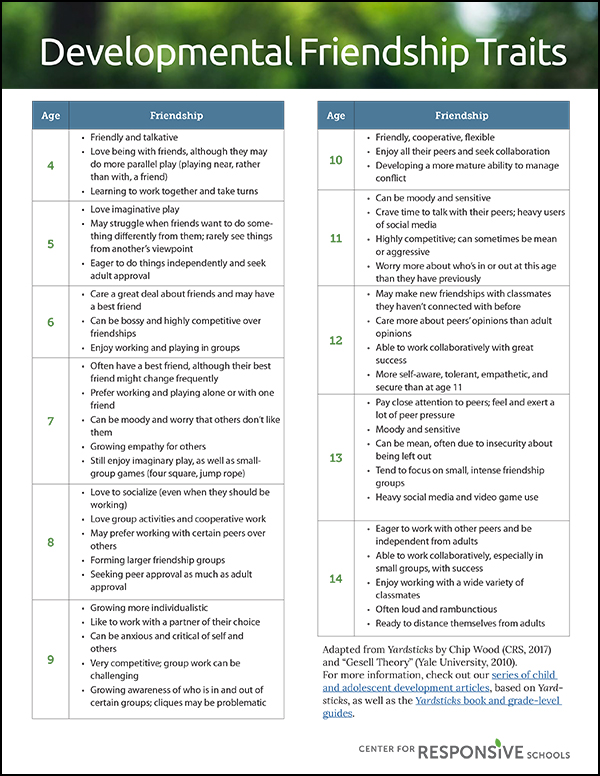

Be aware of developmental needs. Children grow and develop physically, cognitively, socially, and emotionally at different rates, so within your classroom there will be a wide range of developmental needs, especially related to friendships. The stages of development follow a cyclical pattern, with each cycle moving through six stages and alternating between equilibrium and disequilibrium (Gesell Theory, 2010). These patterns are related to the way the brain grows and develops in spurts (you can find more information related to this in Chip Wood’s Yardsticks (2017). In terms of friendship specifically, at ages eight and ten you’ll notice periods of relative equilibrium related to peers, when students often enjoy larger friendship groups, fewer conflicts, and cooperative activities. By contrast,

nine- and eleven-year-olds tend to be in transitional disequilibrium, when you might see moody behavior, more frequent conflicts, and exclusive friendships. Development changes aren’t in lockstep with the calendar, so different students will exhibit different behaviors at different times—but all children progress through the same stages at some point.

Set your classroom up to fit who your students are and what they need. Children learn best when the physical classroom space reflects their developmental characteristics, including their social, emotional, cognitive, and physical needs. When you design your classroom to leverage these characteristics, you not only support academic growth but also strengthen peer connections. Imagine wall displays that celebrate students’ families and backgrounds, flexible seating arrangements that support interactive learning, and classroom libraries with enough space for students to browse together—all opportunities for students to connect and share with each other in the natural course of a day in your classroom.

Teach empathy. It’s natural for us to be better friends with certain people than with others. Studies show that friendships are often built on similarities; we are more prone to connect with people who are already similar to ourselves in some way. Students don’t have to be friends with every single person they encounter, of course, but having empathy for others—especially those who are different from themselves—is crucial. As much as possible, teach empathy skills explicitly. Help students to recognize their own emotions and the emotions of others, to be aware of the impact their actions have on others, and to respect and value diversity and different cultural norms in others. Your English language arts, history, and social studies lessons are great places to embed discussions about empathy. Asking students to put themselves in the shoes of the characters or historical figures you are learning about is an effective way to encourage meaningful conversations about empathy. Creative projects, such as creating a mock Twitter account for a historical figure or writing a new scene or ending for a book, can do double duty as authentic assessment tasks and meaningful exercises in empathy.

Model friendship skills. Your students are always watching you. When you interact with another adult, they’re paying attention and taking their cues from you. Do you make eye contact and greet other adults by name as your class walks by in the hallway? Are you quick to offer help to your colleagues and accept help from them? Show your students through your own actions what it looks like to be a good friend and how much you value being kind and respectful to all peers.

Help students work together with interactive learning structures. Great cognitive growth occurs through social interaction, which our students crave but don’t always have the skills to manage independently while simultaneously managing their academic work. They need guidance not only for what to work together on but how to work together. Interactive learning structures are hands-on, collaborative frameworks that guide students to work together well and with purpose. Useful for small- and whole-group activities and at any point during a lesson, these structures promote social and cognitive connections.

Provide support when needed at recess. You may often hear from your students that recess is one of their favorite parts of the school day, but what you may not always hear is how stressful some students can find this time because making friends is challenging for them. You can help all of your students find fun, inclusive activities and connect with their peers during recess if you spend some time teaching and modeling recess skills such as initiating a game, asking someone to join you, and seeking help when needed. These skills are especially important during the first days and weeks of the school year as classmates get to know one another. Consider teaching a game during your Morning Meeting that students can reprise during recess or joining your students for a few minutes of recess to get a new game started. Check-in with students after recess to see what worked well and what they’d like to work on next time.

Normalize conflicts—and how to solve them. It’s important for students to recognize that conflict is a natural part of life, especially in close friendships. Learning how to advocate for oneself, solve problems, and respect different opinions are lifelong skills that everyone—children and adults alike—benefits from through practice. These skills need to be intentionally taught and modeled before students can practice them independently. Caltha Crowe, Responsive Classroom consulting teacher and author, suggests five skills to start with:

- Cooling off when upset

- Speaking directly to each other

- Speaking assertively, honestly, and kindly

- Listening carefully to others and accurately paraphrasing their words

- Proposing solutions and agreeing on a solution to try (Crowe, 2009)

Learn more about Caltha’s approach to teaching conflict resolution here or in her book Solving Thorny Behavior Problems: How Teachers and Students Can Work Together (Center for Responsive Schools, 2018).

Talk about how to be friends. Make conversations about building and maintaining friendship a normal part of everyday life in your classroom. As you help students recognize, appreciate, and work on the skills needed to be a good friend, they will gradually begin to do this type of metacognitive reflection independently. Literature can be a wonderful entry point into these discussions. As you read books as a class, whether as read-alouds, in book groups, or as independent reading, bring students’ awareness to the specific friendship skills, conflicts, or dilemmas in the books. Students can make text-to-self connections, build empathy, and even role-play different scenarios, all while building reading comprehension.

Partner with parents. Friendships and peer pressure are understandably high on parents’ list of worries for their children. Letting parents know what to expect developmentally, the social skills and problem-solving strategies you’re teaching in your classroom, and their child’s particular strengths and areas for growth related to friendship will not only ease some of those worries but will also provide parents with tools for supporting their children. In turn, parents are valuable resources for teachers, as they know their children better than anyone and can offer great insights into past experiences and current happenings. Working together, parents and teachers are an unbeatable team.

These ten tips will help you cultivate the conditions for friendship in your classroom and encourage your students to build strong connections that will continue long after the school year ends.

Great Picture Books About Friendship

- Each Kindness written by Jacqueline Woodson, illustrated by E.B. Lewis

- Little Blue and Little Yellow by Leo Lionni

- Lost and Found by Oliver Jeffers

- The New Bird in Town written by Jamie Deenihan, illustrated by Carrie Hartman Click here for a free lesson plan

- Owen & Mzee: The True Story of a Remarkable Friendship written by Isabella Hatkoff, Craig Hatkoff, and Dr. Paula Kahumbu, with photographs by Peter Greste

- Strictly No Elephants written by Lisa Mantchev, illustrated by Taeeun Yoo

- The Hike by Alison Farrell

Great Chapter Books About Friendship

- 11 Birthdays by Wendy Mass

- Alexis vs. Summer Vacation by Sarah Jamila Stevenson, illustrated by Veronica Agarwal Click here for a free lesson plan

- Be Prepared by Vera Brosgol

- Look Both Ways: A Tale Told in Ten Blocks by Jason Reynolds

- Save Me a Seat by Sarah Weeks and Gita Varadarajan

- The Season of Styx Malone by Kekla Magoon

- The Way to Bea by Kat Yeh

References

- Crowe, C. (2009, February 1). “Coaching children in handling everyday conflicts.” Center for Responsive Schools. https://www.responsiveclassroom.org/coaching-children-in-handling-everyday-conflicts/

- “Gesell Theory.” 2010. Gesell Program in Early Childhood, Yale University. https://www.gesell-yale.org/pages/gesell-theory

- Wood, C. (2017). Yardsticks: Child and adolescent development ages 4–14, 4th ed. Center for Responsive Schools.