Bringing hope and joy to educators and students.

We strive to influence and inspire a world-class education for

every student in every school, every day.

Our Programs

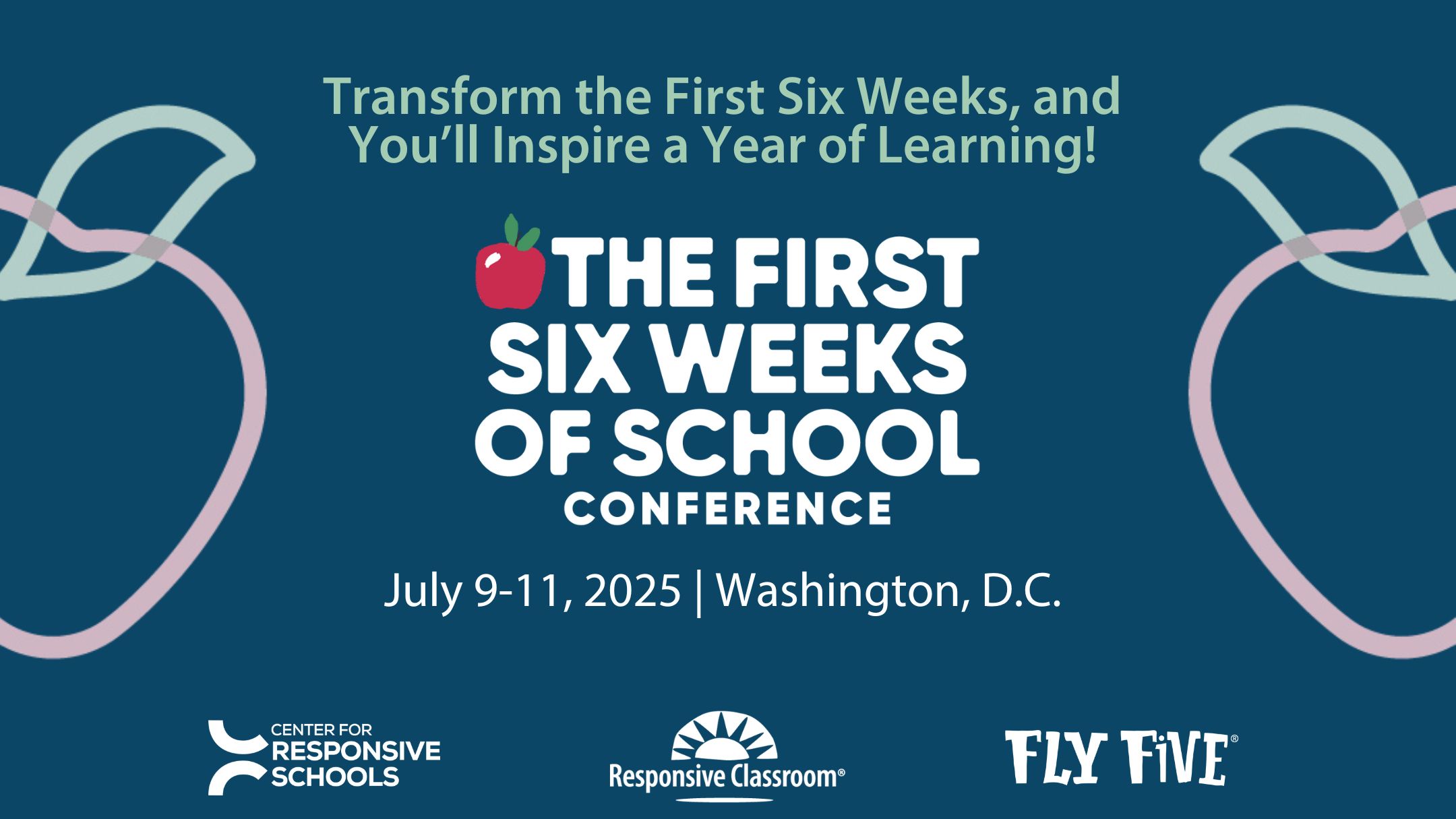

Responsive Classroom is an evidence-based approach to teaching and discipline that focuses on engaging academics, positive community, effective management, and developmental awareness. Our professional development, books and resources help elementary and middle school educators to create safe, joyful, and engaging classrooms and school communities where students develop strong social and academic skills and every student can thrive.

Fly Five is a kindergarten to eighth grade social and emotional learning curriculum developed on the core belief that, in order for students to be academically, socially, and behaviorally successful in, out of, and beyond school, they need to learn a set of social and emotional competencies, namely cooperation, assertiveness, responsibility, empathy, and self-control (C.A.R.E.S.). The Fly Five lessons are intentionally designed to be easy to follow and implement so that teachers can place their attention on the important work of noticing a student’s academic, social, and emotional growth and progress and creating conditions for that progress to continue.